| SDSS Classic |

| SDSS.org |

| SDSS4.org |

| SDSS3.org |

| SDSS Data |

| DR19 |

| DR17 |

| DR10 |

| DR7 |

| Science |

| Press Releases |

| Education |

| Image Gallery |

| Legacy Survey |

| SEGUE |

| Supernova Survey |

| Collaboration |

| Publications |

| Contact Us |

| Search |

April 26, 2005

SDSS uses 200,000 quasars to confirm Einstein's prediction of cosmic magnification

Applying cutting edge computer science to a wealth of new astronomical data, researchers from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey (SDSS) reported today the first robust detection of cosmic magnification on large scales, a prediction of Einstein's General Theory of Relativity applied to the distribution of galaxies, dark matter, and distant quasars.

These findings, accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, detail the subtle distortions that light undergoes as it travels from distant quasars through the web of dark matter and galaxies before reaching observers here on Earth.

The SDSS discovery ends a two decade-old disagreement between earlier magnification measurements and other cosmological tests of the relationship between galaxies, dark matter and the overall geometry of the universe.

"The distortion of the shapes of background galaxies due to gravitational lensing was first observed over a decade ago, but no one had been able to reliably detect the magnification part of the lensing signal", explained lead researcher Ryan Scranton of the University of Pittsburgh.

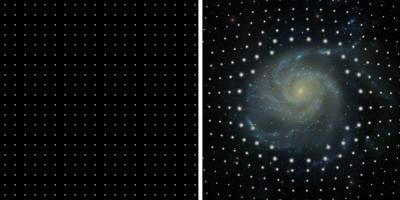

As light makes its 10 billion year journey from a distant quasar, it is deflected and focused by the gravitational pull of dark matter and galaxies, an effect known as gravitational lensing. The SDSS researchers definitively measured the slight brightening, or "magnification" of quasars and connected the effect to the density of galaxies and dark matter along the path of the quasar light. The SDSS team has detected this magnification in the brightness of 200,000 quasars.

While gravitational lensing is a fundamental prediction of Einstein's General Relativity, the SDSS collaboration's discovery adds a new dimension.

"Observing the magnification effect is an important confirmation of a basic prediction of Einstein's theory," explained SDSS collaborator Bob Nichol at the University of Portsmouth. "It also gives us a crucial consistency check on the standard model developed to explain the interplay of galaxies, galaxy clusters and dark matter."

Astronomers have been trying to measure this aspect of gravitational lensing for two decades. However, the magnification signal is a very small effect — as small as a few percent increase in the light coming from each quasar. Detecting such a small change required a very large sample of quasars with precise measurements of their brightness.

"While many groups have reported detections of cosmic magnification in the past, their data sets were not large enough or precise enough to allow a definitive measurement, and the results were difficult to reconcile with standard cosmology," added Brice Menard, a researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, NJ.

The breakthrough came earlier this year using a precisely calibrated sample of 13 million galaxies and 200,000 quasars from the SDSS catalog. The fully digital data available from the SDSS solved many of the technical problems that plagued earlier attempts to measure the magnification. However, the key to the new measurement was the development of a new way to find quasars in the SDSS data.

"We took cutting edge ideas from the world of computer science and statistics and applied them to our data," explained Gordon Richards of Princeton University.

Richards explained that by using new statistical techniques, SDSS scientists were able to extract a sample of quasars 10 times larger than conventional methods, allowing for the extraordinary precision required to find the magnification signal. "Our clear detection of the lensing signal couldn't have been done without these techniques," Richards concluded.

Recent observations of the large-scale distribution of galaxies, the cosmic microwave background and distant supernovae have led astronomers to develop a "standard model" of cosmology. In this model, visible galaxies represent only a small fraction of all the mass of the universe, the remainder being made of dark matter.

But to reconcile previous measurements of the cosmic magnification signal with this model required making implausible assumptions about how galaxies are distributed relative to the dominant dark matter. This led some to conclude that the basic cosmological picture was incorrect or at least inconsistent. However, the more precise SDSS results indicate that previous data sets were likely not up to the challenge of the measurement.

"With the quality data from the SDSS and our much better method of selecting quasars, we have put this problem to rest," Scranton said. "Our measurement is in agreement with the rest of what the universe is telling us and the nagging disagreement is resolved."

"Now that we've demonstrated that we can make a reliable measurement of cosmic magnification, the next step will be to use it as a tool to study the interaction between galaxies, dark matter, and light in much greater detail," said Andrew Connolly of the University of Pittsburgh.

AUTHORS:

- Ryan Scranton, University of Pittsburgh

- Brice Menard, Institute for Advanced Study

- Gordon T. Richards, Princeton University

- Robert C. Nichol, University of Portsmouth

- Adam D. Myers, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

- Bhuvnesh Jain, University of Pennsylvania

- Alex Gray, Carnegie Mellon University

- Matthias Bartelmann, Max-Planck-Institute for Astronomy

- Robert J. Brunner, University of Illinois

- Andrew J. Connolly, University of Pittsburgh

- James E. Gunn, Princeton University

- Ravi K. Sheth, University of Pennsylvania

- Neta A. Bahcall, Princeton University

- John Brinkman, Apache Point Observatory

- Donald P. Schneider, Pennsylvania State University

- Ani Thakar, Johns Hopkins University

- Donald G. York, University of Chicago

CONTACTS:

- Ryan Scranton, University of Pittsburgh, scranton@bruno.phyast.pitt.edu, 412-600-1914

- Brice Menard, Institute for Advanced Study, menard@ias.edu, 609-734-8013

- Gordon Richards Princeton University, gtr@astro.princeton.edu, 609-258-3578

- Robert Nichol, University of Portsmouth, bob.nichol@port.ac.uk, (44)023-928-3117

- Gary S. Ruderman, Public Information Officer, Sloan Digital Sky Survey, sdsspio@aol.com, 312-320-4794